Back to: ASP.NET Core Web API Tutorials

HTTP (HyperText Transport Protocol)

In this article, I will discuss everything you need to know about HTTP (HyperText Transport Protocol), i.e., HTTP Verbs or Methods, HTTP Status Codes, HTTP Requests, and Responses. Please read our previous article discussing ASP.NET Core Web API Introduction.

Hypertext Transfer Protocol

The Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is the foundation of communication on the World Wide Web, enabling interaction between clients and servers. It defines how requests and responses are exchanged, ensuring that resources such as web pages, images, stylesheets, and APIs are delivered correctly and efficiently.

Whether you are browsing a website, using a mobile app, or consuming an API, HTTP is the protocol that enables the exchange of information. A solid understanding of HTTP is essential not only for web developers but also for testers, network engineers, and anyone working with internet-based applications, as it provides the groundwork for building secure, scalable, and optimized systems.

What is HTTP?

HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) is the backbone of data communication on the web. It defines the rules for how clients (like browsers or apps) send requests to servers and how servers respond with data. This protocol ensures that when you access a website, the content (HTML, images, CSS, scripts) is transmitted properly between your device and the server hosting the site. HTTP works as a request–response protocol where the client initiates communication and the server fulfills it.

Important Points

- HTTP stands for Hypertext Transfer Protocol.

- It is the foundation of communication on the World Wide Web.

- Defines how messages are formatted and transmitted.

- Enables browsers, apps, and tools to send requests and receive responses.

- Operates in a client–server model.

Example

When you type https://www.example.com into your browser and press Enter:

- The browser sends an HTTP Request to the server hosting example.com.

- The server replies with an HTTP Response containing the HTML page.

- The browser then displays that page to you.

Why do we need to know about HTTP?

Understanding HTTP is crucial for anyone involved in web development or internet-based applications because it is the core protocol of the internet. Whether you are a developer building a website, an engineer troubleshooting network issues, or a tester analysing APIs, knowing HTTP helps you communicate more effectively with web systems. It also provides insight into how requests and responses behave, how to debug errors, and how to design more effective applications.

Important Points

- Web Development: Helps build efficient and optimized applications.

- API Integration: Helps in consuming and building RESTful APIs.

- Troubleshooting: Familiarity with HTTP status codes (such as 200 OK, 404 Not Found, and 500 Internal Server Error) aids in debugging issues.

- Performance: Knowledge of caching headers and connection types helps optimize speed.

- Security: Understanding secure communication (HTTPS) prevents data leaks.

- Debugging: Makes it easier to trace and fix issues using HTTP status codes and headers.

Example: If a webpage fails to load and displays a “404 Not Found” error, a developer who understands HTTP knows that the server cannot locate the requested resource. This makes it easier to fix the broken link or update the resource path.

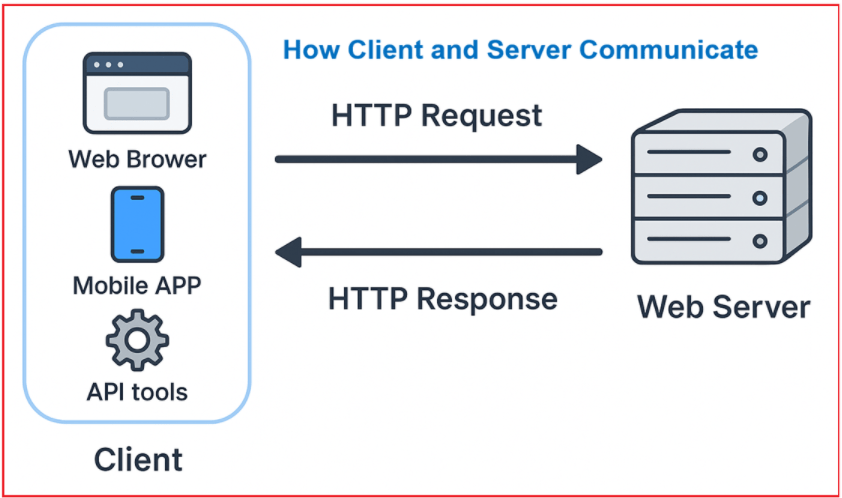

How Client and Server Communicate

Communication between a browser (client) and a web server occurs through HTTP, in the form of requests and responses, within a client–server architecture. The browser (or any client) sends a request when you try to access a resource, and the server responds with the requested data. This communication is not limited to browsers, mobile apps, or tools like Postman; other systems can also act as clients. Every request you send is an HTTP Request, and every piece of data returned is an HTTP Response.

Important Points

- Client: Browser, mobile app, or tool (like Postman, Swagger, Fiddler).

- Server: Hosts the web application or API.

- Request: Data sent from client to server (e.g., asking for a webpage or JSON data).

- Response: Data sent from the server to the client (e.g., HTML page, JSON).

- Protocol: Communication is possible only through HTTP/HTTPS.

Example

You open a shopping app on your phone and view a product.

- Your mobile app sends an HTTP Request to the server asking for product details.

- The server replies with an HTTP Response containing the product name, price, and images.

- The app then displays this information to you.

This mechanism ensures a smooth interaction between clients (browsers, mobile apps, and API tools) and servers, enabling web applications to function correctly.

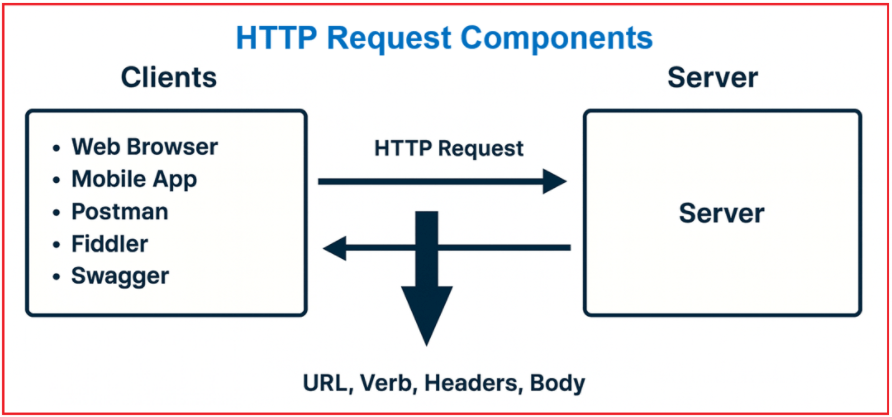

HTTP Request Components

An HTTP Request is the message sent by the client (browser, mobile app, Postman, Swagger, etc.) to the server asking for a resource or action. Every request must follow a specific structure so that the server can understand what the client needs. It consists of a request line, headers, an optional body, and sometimes query parameters in the URL. Together, these components define what resource is being requested, how it should be processed, and any additional data or context needed. For a better understanding, please have a look at the following diagram:

Request Line:

The Request Line is the first line of an HTTP request and specifies to the server the exact action the client wants to perform, the resource it is targeting, and the HTTP version it supports. It always contains three parts:

HTTP Method: This represents the type of operation the client wants to perform on the server. For example:

- GET → Retrieve a resource without making changes (e.g., viewing a webpage).

- POST → Send new data to the server for processing (e.g., submitting a login form).

- PUT → Update an existing resource completely.

- DELETE → Remove a resource from the server.

- Other methods include PATCH (Partial Update), HEAD (request headers only), and OPTIONS (check supported methods).

Request Target / URL: This indicates the resource location. It could be:

- A Full URL (like https://example.com/index.html), or

- A Relative path (like /index.html) when the server domain is already specified in the headers.

HTTP Version: Tells the server which version of HTTP the client is using.

- For example: HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2, or the newer HTTP/3.

- This matters because different versions support different features. Understanding features is beyond the scope of this session.

Example: GET https://example.com/index.html HTTP/1.1

Request Headers:

After the request line, the client usually sends one or more headers. These headers serve as additional instructions, providing more detailed descriptions of the request. They are written in key-value format (e.g., Host: www.example.com) and each appears on a separate line. Common request headers include:

- Host: Specifies the domain name of the target server (Host: www.example.com).

- User-Agent: Identifies the client software making the request (e.g., browser, mobile app, Postman, etc.).

- Accept: Lists the content types the client is willing to accept from the server (e.g., HTML, JSON, XML).

- Content-Type: When the request includes a body (like a POST, PUT, or PATCH request), this header indicates the format of the request body. Example: application/json, application/xml, etc.

- Authorization: Carries credentials, such as API keys or tokens, for authentication.

- Cookie: Includes any cookies previously stored by the browser to maintain sessions. This is used for state management.

- Cache-Control: Provides caching rules for both client and server.

Example:

- Host: www.example.com

- User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/91.0.4472.124 Safari/537.36

- Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Request Body (Optional):

The request body is the part of an HTTP request that carries data from the client to the server.

- The body of an HTTP request is optional and is generally used in methods such as POST, PUT, and PATCH, where the client needs to send data to the server for processing.

- The data can also be:

- Form submissions (e.g., login details).

- File uploads (images, PDFs).

- JSON or XML payloads for APIs.

Example Body (JSON in a POST Request):

For instance, in a POST request, the body would contain the JSON data as follows.

{

"Username": "ExampleUser",

"Password": "ExamplePass"

}

Query Parameters:

Query parameters are part of the URL itself. They are used to send extra details to the server in the form of key-value pairs.

- They start with a question mark (?).

- They are sent in the form of a key-value pair.

- Multiple parameters are separated by an ampersand (&).

- These parameters are beneficial for search, filtering, sorting, or pagination operations on the server.

Example URL with Query Parameters:

https://example.com/search?q=example&sort=asc

- q=example: The query parameter q has the value example.

- sort=asc: The query parameter sort has the value asc.

HTTP Response Components

An HTTP response is the message sent from the Server back to the Client after processing a request. The response informs the client whether the request was successful or not and may also include the requested content or an error message. An HTTP response is composed of a Status Line, Response Headers, and optionally, a Response Body. This response structure is crucial for the client to understand what action the server took and what data is being returned. For a better understanding, please have a look at the following diagram:

Response Line:

The Response Line (also known as the Status Line) is the first line of an HTTP response. It provides the client with essential information about the response that the server is sending back. It is always made up of three parts:

HTTP Version: Tells the client which version of HTTP the server is using. Common versions include HTTP/1.1 (still widely used), HTTP/2 (faster with multiplexing), and HTTP/3 (the latest, offering improved performance and security).

Status Code: A three-digit number that represents the outcome of the client’s request. The Status codes are grouped into categories:

- 1xx (Informational): Request received, processing continues.

- 2xx (Success): Request was successful (e.g., 200 OK, 201 Created).

- 3xx (Redirection): Client must take additional steps (e.g., 301 Moved Permanently).

- 4xx (Client Errors): The request has an error (e.g., 400 Bad Request, 404 Not Found).

- 5xx (Server Errors): The server failed to process the request (e.g., 500 Internal Server Error).

Status Text: A short, human-readable description of the status code (e.g., OK for 200, Not Found for 404).

Example Response Line: HTTP/1.1 200 OK

This means:

- The server used HTTP version 1.1,

- The status code is 200 (success),

- The status text is OK.

Response Headers:

Each HTTP Response can have one or more Response Headers. The Response Headers come immediately after the response line and are composed of key-value pairs. These headers provide additional information about the response and the server. Each header is on its own line. Common response headers include:

- Content-Type: Specifies the type of data in the response body (e.g., text/html for webpages, application/json for APIs).

- Content-Length: Specifies the size of the response body in bytes (helps the client know how much data to expect).

- Server: Provides information about the server software that handled the request (e.g., Apache, Nginx, IIS, Kestrel, etc.).

- Set-Cookie: Used to send cookies from the server to the client browser. This is useful for session management and personalization.

- Cache-Control: Tells the client or proxy how caching should be handled (e.g., store for a day, don’t cache at all).

- Date: The timestamp when the server sent the response.

Example Response Headers:

- Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

- Content-Length: 138

- Server: Apache/2.4.41 (Ubuntu)

Response Body:

The Response Body is the part of the HTTP response that carries the actual data being returned to the client. Whether or not a body is included depends on the request method and the status code. For example:

- A GET request typically includes a body containing the requested content.

- A 204 No Content response intentionally has no body.

The data in the response body can be in various formats, such as:

- HTML (for rendering web pages),

- JSON or XML (for APIs),

- Plain text,

- Images, files, or other media types.

The format and presence of the body depend on the Content-Type header sent by the server.

Example JSON Response Body:

The following is a typical response from a REST API endpoint that returns user details.

{

"Id": 123,

"Name": "John Doe",

"Email": "john.doe@example.com"

}

HTTP Verbs or HTTP Methods:

HTTP Methods (also known as HTTP Verbs) define the type of operation a client wishes to perform on a resource in a web server. Each HTTP request must use one of these methods to instruct the server about the intended action, such as retrieving data, creating a new record, updating existing data, or deleting a resource. Let us understand what all HTTP Methods or Verbs are available.

GET HTTP Method:

The GET method is the most commonly used HTTP method. It is designed to retrieve information from the server without changing anything on the server. Since it is a read-only operation, GET is both safe and idempotent, meaning that multiple identical GET requests will always yield the same result without any side effects. It is typically used for fetching web pages, images, JSON API data, or any resource that can be displayed or consumed.

Important Points:

- Idempotent: Yes (Multiple identical GET requests will have the same effect as a single request).

- Safe: Yes (does not modify data on the server).

- Request Body: No (bodies are ignored).

- Typical Use Cases: Fetching resources like HTML pages, JSON data, and images.

- Since GET is both safe and idempotent, it is predictable and can be repeated without side effects.

Example:

- GET /articles HTTP/1.1

- Host: example.com

POST HTTP Method:

The POST method is used to send data to the server, usually resulting in the creation of a new resource or triggering a process. Unlike GET, it modifies the server state by adding or processing data. Since multiple POST requests with the same data can create duplicates, POST is not idempotent. It is widely used for form submissions, file uploads, and creating new records in APIs.

Important Points:

- Idempotent: No (Multiple identical POST requests can result in multiple resources being created or multiple operations being performed).

- Safe: No (POST requests typically modify server state by creating or updating resources).

- Request Body: Yes (data is sent in the request body, e.g., JSON, XML, form data).

- Typical Use Cases: Submitting forms, uploading files, and creating records.

Example:

POST /articles HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

Content-Type: application/json

{

"Title": "New Article",

"Content": "This is the content of the new article."

}

PUT HTTP Method:

The PUT method is used to completely update or replace an existing resource with the new data provided in the request body. If the resource does not exist, some servers may create it; however, the primary purpose is typically to perform a complete update or replacement of the existing resource. PUT is idempotent; sending the same request multiple times results in the same final state. For example, updating all fields of a product in a database would be accomplished with a PUT request.

Important Points:

- Idempotent: Yes/No (Sending the same PUT request multiple times should have the same final effect as sending it once).

- Safe: No (PUT requests modify server state by updating or creating resources).

- Request Body: Yes (Contains the complete representation of the resource to be updated).

- Typical Use Cases: Updating/replacing entire resources.

Example:

PUT /articles/101 HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

Content-Type: application/json

{

"Id": 101,

"Title": "Updated Article",

"Content": "This is the updated content of the article."

}

Note: Ensure the ID in the URL path (/articles/101) matches the resource identifier in the body (“Id”: 101) if your API design requires it.

PATCH HTTP Method:

The PATCH method is used for Partial Updates to an existing resource. Unlike PUT, which replaces the entire resource, PATCH updates only the fields provided in the request body. This makes PATCH more efficient when only a subset of data needs to be changed. Whether PATCH is idempotent depends on implementation; some designs ensure it is, others do not.

Important Points:

- Idempotent: It depends on the implementation. If the patch request is designed so that multiple identical PATCH requests yield the same result, it can be idempotent. However, in many real-world cases, PATCH can be non-idempotent (e.g., if each call increments a value).

- Safe: No (It modifies the state of the server).

- Request Body: Yes (Contains only the data (fields) you want to change).

- Typical Use Cases: Updating specific fields of a record (e.g., only content in an article).

Example:

PATCH /articles/1 HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

Content-Type: application/json

{

"Content": "This is the updated content of the article."

}

Note: Commonly, you do not include the resource’s ID in the body if the ID is already specified in the URL, unless your API design specifically requires it.

DELETE HTTP Method:

The DELETE method is used to remove a resource from the server. Once deleted, attempting to access the same resource should ideally return a 404 Not Found error or indicate that it’s inactive. DELETE is idempotent; repeating the same DELETE request has the same effect: the resource remains deleted. Many applications use either soft delete (marking an item as inactive) or hard delete (permanently removing an item).

Important Points:

- Idempotent: Yes (resource remains deleted).

- Safe: No (modifies server state).

- Request Body: Usually No (the resource is specified in the URL). If you are performing a bulk deletion operation, the request body can be included.

- Typical Use Cases: Removing records, files, or resources.

Example:

- DELETE /articles/1 HTTP/1.1

- Host: example.com

Deletion Strategies:

In modern applications, we can implement Delete Functionality in two ways: Soft Delete and Hard Delete.

- Soft Delete: In your table, if you have a column like IsDeleted, IsActive, or something similar to this, and you want to update that column to false when a delete operation is performed. In that case, instead of using DELETE, you need to use the PATCH method. This is because we are not deleting the record from the database; instead, we are simply updating it.

- Hard Delete: To remove an existing entity from the table, use the DELETE method. For example, delete an existing product from the Product table in the database, etc.

HTTP HEAD Method:

The HEAD method is almost identical to GET, but only requests the headers, not the body. It helps check whether a resource exists, determine metadata (like size or type), or validate caching without downloading the entire content.

Important Points:

- Idempotent: Yes.

- Safe: Yes.

- Request/Response Body: No (no body sent or returned).

- Typical Use Cases: Checking metadata before downloading a resource.

Example:

- HEAD /articles HTTP/1.1

- Host: example.com

HTTP OPTIONS Method:

The OPTIONS method informs the client about the available communication options (HTTP methods, headers, etc.) for a specific resource. It is essential in CORS (Cross-Origin Resource Sharing) scenarios, where browsers send a preflight request with the OPTIONS method to check if the actual request is permitted from another origin before sending the actual request.

Important Points:

- Idempotent: Yes.

- Safe: Yes.

- Response Body: Optional (may describe available communication options).

- Typical Use Cases: Checking allowed methods, used in CORS preflight.

Example:

- OPTIONS /articles HTTP/1.1

- Host: example.com

What do you mean by Idempotent Methods?

An HTTP method is called idempotent when performing the same request multiple times produces the same final result on the server as performing it once. The key idea is that repeating the request does not alter the resource’s state further after the first execution. For example, updating a record with the same data repeatedly will still result in the same final resource. However, this does not mean the server won’t respond differently (e.g., it may return the same status code or additional headers each time). What matters is that the resource state remains consistent.

Important Points

- Idempotency = Same final state even if executed multiple times.

- Examples of idempotent methods:

- GET → Fetching a resource repeatedly doesn’t change it.

- PUT → Updating a resource with duplicate content multiple times keeps it in the same state.

- DELETE → Deleting a resource multiple times still leaves it deleted.

- HEAD / OPTIONS → Repeated calls return the same meta-information.

- POST is NOT idempotent → Each repeated request may create a new record.

Example (Idempotent): PUT Request:

PUT /users/10

{

"Name": "John Doe",

"Email": "john@example.com"

}

Here,

- First execution updates user 10.

- Second, third, or hundredth execution → still results in user 10 having the same name and email.

- Same final state → Idempotent.

What do you mean by Safe Methods?

An HTTP method is called safe when it is intended only for retrieving information and does not modify the server’s state. Safe methods are “read-only,” meaning that even if they are executed multiple times, they should not have any side effects, such as creating, updating, or deleting resources. They are designed so that clients (like browsers, crawlers, or API testers) can call them freely without worrying about unintended changes to the application.

Important Points

- Safe methods = Do not modify data on the server.

- Examples of safe methods:

- GET → Retrieve a webpage or resource.

- HEAD → Get headers only, without body.

- OPTIONS → Ask which methods are allowed, no data modification.

- Can be repeated without risk of altering the server’s state.

- Helpful for browsing, searching, or checking metadata.

Example (Safe): GET Request:

GET /products/100

- Returns details of product 100.

- Calling it once or a hundred times will not alter product 100.

- Data remains unchanged → Safe.

HTTP Status Code Categories:

HTTP status codes are three-digit numbers sent by the server in an HTTP response. They inform the client whether the request was successful, requires further action, or has failed due to an error. Understanding them helps in debugging APIs, monitoring web apps, and ensuring proper communication between clients and servers. These codes are grouped into five categories based on the first digit. They are as follows: Here, XX will represent the actual number.

- 1xx (Informational Responses): Request received; server is working on it.

- 2xx (Successful Responses): Request understood and successfully processed.

- 3xx (Redirection Responses): Further action is needed to complete the request.

- 4xx (Client Error Responses): There was an issue with the client’s request.

- 5xx (Server Error Responses): The server encountered an issue processing the request.

1XX: Informational Response Status Codes

The 1xx category represents informational responses. These indicate that the server has received the request and is continuing to process it, but no final response has been sent yet. They are not commonly seen in normal web browsing, but are essential in advanced scenarios, such as long-running requests or large file uploads, where the server needs to acknowledge progress.

Important Points:

- It tells the client that the request has been received and that processing continues.

- Temporary, not final responses.

- Often used in special situations, such as chunked uploads or long-running tasks.

Examples:

- 100 Continue → Server acknowledges headers and asks the client to send the request body (useful before sending large data).

- 102 Processing → Server is still working on the request, but hasn’t finished (used in WebDAV and long tasks).

Real-Life Example: When uploading a large file, the client first sends headers. The server responds with a 100 Continue, indicating that the client can proceed with sending the file contents.

2XX: Successful Response Status Codes

The 2xx category indicates that the client’s request was successfully received, understood, and processed. These are the most common codes used during normal web usage, confirming that the requested action was completed.

Important Points:

- It confirms successful request handling.

- Final responses (unlike 1xx).

- Often include requested data in the response body.

Examples:

- 200 OK: The standard response for successful HTTP requests. The requested resource (or data) is usually returned in the response body. For example, retrieving a web page or fetching data from an API.

- 201 Created: The request was successful, and a new resource was created as a result. It is commonly used for POST requests. For example, creating a new user account or posting a new article.

- 202 Accepted: The request has been accepted for processing, but it has not yet been completed. This is often used for asynchronous tasks. For example, initiating a background job or asynchronous task.

- 204 No Content: The server successfully processed the request and is not returning any content. Often used after a successful DELETE or PUT operation when there is no need to return data. For example, deleting a resource or updating a record without returning the updated data.

Real-Life Example: When you register on a site, the API might return 201 Created with the new user ID.

3XX: Redirection Response Status Codes

The 3xx category indicates that the client must take further action to complete the request, typically by making another request to a different location. These codes are essential for redirecting users or handling resource movements, such as when websites change their domain names.

Important Points:

- It guides the client to a new resource location.

- Often include a Location header with the new URL.

- Common in SEO, domain migrations, and temporary site changes.

Examples:

- 301 Moved Permanently: The resource has been permanently moved to a new URI provided in the Location header. The Ideal use case is redirecting from an old domain to a new one. Future requests should use the new URI.

- 302 Found: The resource is temporarily located at a different URI. The client should use the new URI for this request, but future requests can still use the original URI. An ideal use case is temporary redirection during maintenance.

Real-Life Example: If you type http://example.com, the server may respond with 301 Moved Permanently to redirect you to https://example.com.

4XX: Client Error Response Status Codes

The 4xx category indicates that the client made an error in the request. These errors are caused by incorrect input, unauthorized access, or asking for resources that don’t exist. They help developers or users know what went wrong with their request.

Important Points:

- It indicates issues caused by the client’s request.

- Common in API development and website usage.

- Client must fix the request before retrying.

Examples:

- 400 Bad Request: The server cannot process the request due to malformed syntax or invalid data. For example, sending malformed JSON in a POST request.

- 401 Unauthorized: Authentication is required and has failed or has not been provided. For example, accessing a protected resource without valid credentials.

- 403 Forbidden: The server understands the request but refuses to authorize it. For example, accessing a resource without sufficient permissions.

- 404 Not Found: The requested resource could not be found on the server. For example, requesting a non-existent webpage or API endpoint.

- 405 Method Not Allowed: The HTTP method used in the request is not supported for the requested resource. For example, sending a PUT request to an endpoint that only supports GET and POST.

Real-Life Example: If you mistype a page URL like /artcles instead of /articles, the server responds with 404 Not Found.

5XX: Server Error Response Status Codes

The 5xx category indicates the request was valid, but the server failed to fulfil it due to an internal problem. These issues are not the client’s fault and typically indicate that the server is misconfigured, overloaded, or temporarily unavailable.

Important Points:

- It shows errors caused by server-side failures.

- Beyond client’s control → require server-side fixes.

- Often retried later by the client.

Examples:

- 500 Internal Server Error: A generic error message indicating an unexpected condition that prevented the server from fulfilling the request. For example, an unhandled exception in server-side code.

- 502 Bad Gateway: The server, while acting as a gateway or proxy, received an invalid response from the upstream server. For example, failures in communication between proxy servers.

- 503 Service Unavailable: The server is currently unable to handle the request due to temporary overload or maintenance. For example, scheduled maintenance periods or unexpected traffic spikes. The client should try the request again later.

- 504 Gateway Timeout: The server, while acting as a gateway or proxy, did not receive a timely response from the upstream server. For example, slow responses from a backend service can lead to a timeout. The client may need to retry the request later.

Real-Life Example: During a high-traffic sale, a website may return a 503 Service Unavailable error because its servers are overloaded.

Conclusion of HTTP

In conclusion, HTTP is far more than just a communication protocol. It is the language of the web. By understanding its building blocks, such as request and response structure, HTTP methods, and status codes, developers and engineers can create applications that are reliable, scalable, and user-friendly. Knowledge of HTTP also makes debugging easier, ensures proper API integration, and enhances application security when combined with HTTPS.

Whether you are building a simple website, a complex web application, maintaining a website, or integrating APIs across platforms, or troubleshooting a network issue, a strong understanding of HTTP fundamentals helps you with the tools needed to work confidently and efficiently in any web-based environment.

In the next article, I will discuss the Creating ASP.NET Core Web API Project using .NET Core CLI Applications. In this article, I explain HTTP (HyperText Transport Protocol) Protocols, i.e., HTTP Requests and Responses. What are HTTP Verbs and some commonly used HTTP Status Codes? And I hope you enjoy this HyperText Transport Protocol article.

Registration Open – Mastering Design Patterns, Principles, and Architectures using .NET

Session Time: 6:30 AM – 08:00 AM IST

Advance your career with our expert-led, hands-on live training program. Get complete course details, the syllabus, and Zoom credentials for demo sessions via the links below.

- View Course Details & Get Demo Credentials

- Registration Form

- Join Telegram Group

- Join WhatsApp Group

Thank you so much for these resources. I am currently trying to get back into the ASP.NET domain so you have no idea how helpful these are. I’ve never delved into Web APIs so I’m starting with .NET Core Web APIs is that ok? Or should I start with the other Web API tutorial on this website?

You can start with ASP.NET Core Web API. No need to learn ASP.NET Web API.

Pls change the heading from transport to transfer protocol.

Hi,

It would be nice to clarify GET Method. where it says “Requests using GET should only be used to request data (they shouldn’t include data)” then later it says

“If you want to implement some kind of search functionality then the Web API may expect some data to filter out the results. In this case, the clients need to send the data.”

so please, you might want to rephrase it to avoid confusion…

reuben

In that case, the method will be GET, and you must pass the data as part of the query string.