Back to: Microservices using ASP.NET Core Web API Tutorials

Circuit Breaker in ASP.NET Core Web API Microservices

In Microservices, one service depends on other services. That means every request may involve network calls (from one service to another via REST or gRPC), and those calls can fail or slow down at any time. The Circuit Breaker Pattern protects our service by stopping repeated calls to an unhealthy dependency, helping our API stay responsive, and preventing failures from spreading across the system.

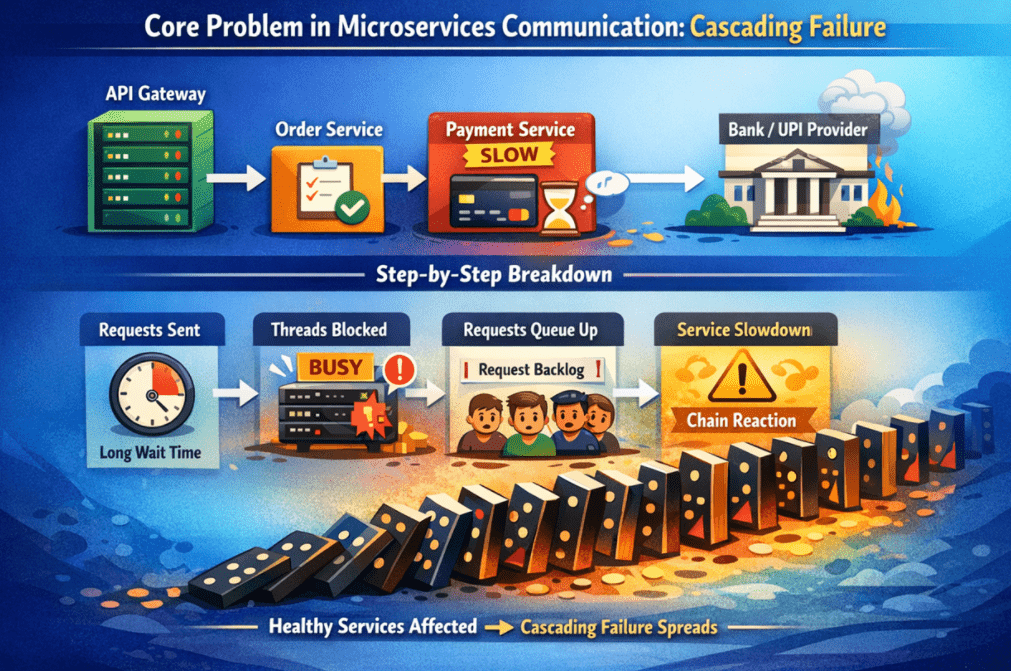

The Core Problem in Microservices Communication: Cascading Failure

In microservices, the real danger is usually Not One Service Failing—it’s what happens after that failure. A single user request often travels through multiple services. For example:

- API Gateway → Order Service

- Order Service → Payment Service

- Payment Service → Bank/UPI Provider

Now imagine the Payment Service Becomes Slow (maybe its database is busy or overloaded). The Order Service still receives the same number of user requests, so it keeps calling the Payment Service repeatedly.

Here is what happens step-by-step:

- The Order Service sends a request to the Payment Service, but the response is delayed.

- The Order Service keeps waiting, so its Threads Remain Busy (Blocked).

- Meanwhile, new user requests keep coming in, so Requests Start Queuing Up.

- Slowly, Order Service becomes slow too—not because it is broken, but because it is stuck waiting.

- After that, any service that depends on Order Service also becomes slow or fails.

- This creates a chain reaction across services, like domains falling one after another.

This chain reaction is called a Cascading Failure—one service problem spreads, making other healthy services appear unhealthy.

So, the core problem is not only that a service fails. The bigger problem is that Healthy services keep calling an unhealthy service, get stuck waiting, and, slowly, the failure spreads to the whole system. That is exactly why we need patterns like Circuit Breaker—to stop the spread of failures early.

A Simple Layman’s Analogy

Imagine a Busy Restaurant.

- Customers keep placing orders (similar to incoming API requests).

- The waiter takes the order and sends it to the kitchen (this is like your service calling a downstream service).

- When the kitchen is fine, food comes quickly, and everything runs smoothly.

Now, assume a key section of the kitchen breaks down (for example, the oven stops working or one of the chefs is unavailable). Cooking becomes slow.

If the waiter keeps sending every new order to that slow kitchen, this happens:

- The kitchen keeps collecting more and more pending orders.

- The waiter keeps standing and waiting for the delayed food.

- Since waiters are stuck waiting, fewer waiters are left to handle new customers.

- Soon, the whole restaurant feels like it has stopped working—even though only one section had a problem.

Now think of a smart restaurant manager who says:

- The kitchen is struggling right now. Stop sending new pizza orders for some time.

- Tell customers pizza is temporarily unavailable (or offer a simpler menu).

- After a short break, try 1–2 test orders to see if the kitchen is back to normal.

That smart manager is the Circuit Breaker. In microservices, a circuit breaker does the same thing: It temporarily stops sending requests to a failing service, so your service doesn’t get stuck waiting, and the rest of the system can continue running.

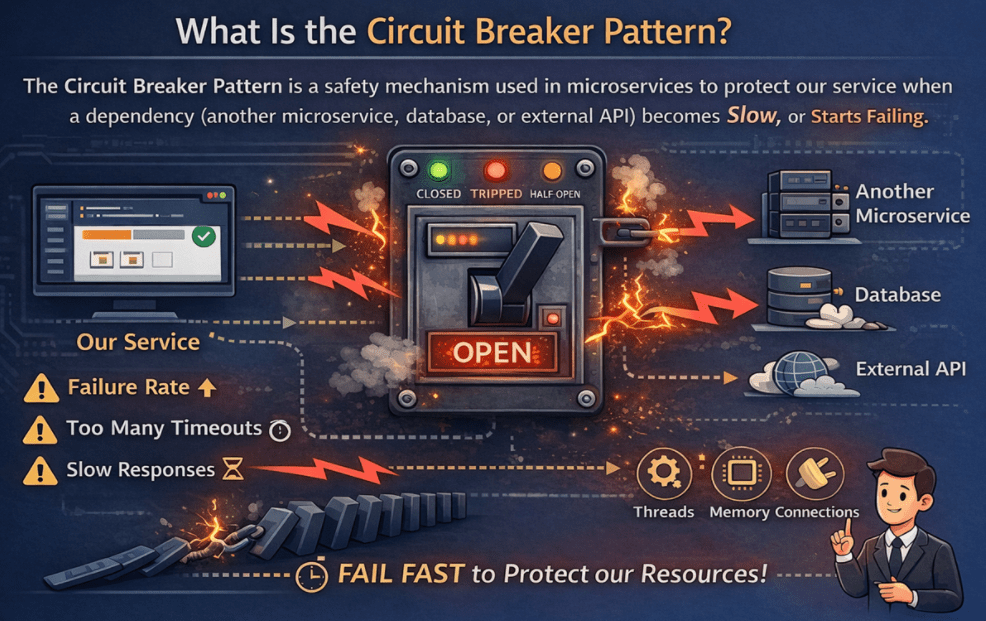

What Is the Circuit Breaker Pattern?

The Circuit Breaker Pattern is a safety mechanism used in microservices to protect our service when a dependency (another microservice, database, or external API) becomes Slow or Starts Failing. Think of it as a protective switch placed around an outgoing call.

In simple words, when our service calls another service, the circuit breaker keeps watching the results of those calls:

- Are we getting too many failures (errors/exceptions)?

- Are we seeing too many timeouts?

- Are responses becoming too slow again and again?

If the dependency looks unhealthy, the circuit breaker opens. Opening means:

- Your service Stops Calling that dependency for a short time.

- It Fails Fast (returns a quick error or a fallback response).

- It saves important resources like Threads, Memory, and Connections.

After a short “Cool-Down” time, the circuit breaker allows a few test calls.

- If the test calls succeed, the circuit closes, and normal calls resume.

- If they fail again, it stays open for a while longer.

The circuit breaker is not meant to guarantee every request succeeds. Its main goal is to keep our overall system stable and responsive and to prevent one unhealthy dependency from taking down other services. Circuit breaker decisions are based on the recent history of calls, not one single failure.

Where Circuit Breaker Fits in ASP.NET Core Web API

In an ASP.NET Core Web API microservice, the Circuit Breaker should be placed exactly where your service calls another system. In other words, it belongs at the outgoing communication boundary, not inside your core business logic. The Circuit breaker is typically applied around:

- HttpClient Calls to other microservices, for example, the Order Service calling the Payment Service.

- gRPC Client Calls

- Third-Party API calls: Payment gateway, SMS/Email provider, OTP service, etc.)

A simple way to visualize placement is:

- Controller receives the request

- Service layer applies business rules

- When it needs data from another service → it calls via HttpClient/gRPC

- Circuit Breaker wraps this outbound call before reaching the downstream dependency

So, the flow becomes: Controller → Service Layer → (Circuit Breaker + HttpClient) → Downstream Service.

So, the breaker sits at the boundary where our service depends on another service, mostly in the Infrastructure Layer of our Microservices. This keeps our business logic clean and keeps resilience concerns in the communication layer.

The Three States of a Circuit Breaker

A Circuit Breaker works like a Traffic Controller between our service and a dependency service. To decide how requests should be handled at any moment, it operates in Three Clear States. Each state represents the circuit breaker’s current belief about the health of the dependency.

Closed State – Normal Operation

The Closed state is the default and normal state of a circuit breaker. In this state:

- All requests are allowed to go to the dependent service

- The circuit breaker does not block anything

- It quietly observes each request and response

- Failures, timeouts, and response times are recorded in the background

The system behaves as if there is no circuit breaker at all. However, the circuit breaker is actively checking whether the dependency is functioning properly or beginning to show problems. Closed does not mean that failures never happen. It simply means that failures are within acceptable limits, and the dependency is still considered usable.

Open State – Protection Mode

When the circuit breaker detects failures or delays that exceed a safe limit, it switches to the Open state. In this state:

- Calls to the dependency are blocked immediately

- No network request is sent

- The service fails fast instead of waiting for timeouts

- System resources, such as threads and connections, are protected

The Open state exists to prevent further damage. It stops a struggling dependency from consuming resources and turning a small issue into a major outage.

In simple terms, the open state means: The dependency is unhealthy right now. Stop calling it to protect the system. This state may temporarily reduce functionality, but it keeps the service responsive and stable.

Half-Open State – Recovery Check

After a short, predefined period, the circuit breaker moves into the Half-Open state. In this state:

- Only a small number of test requests are allowed

- These requests are used to check whether the dependency has recovered

- If the test requests succeed, the circuit breaker closes and normal traffic resumes

- If they fail, the circuit breaker opens again

Half-Open is a careful testing phase. It avoids two extremes:

- Keeping the circuit open forever

- Flooding a recovering service with full traffic too early

This state allows the system to recover automatically, without manual intervention.

In Simple Words

- Closed: Everything looks fine. Let requests flow.

- Open: Things are bad. Stop sending requests.

- Half-Open: Let’s test carefully and decide.

Together, these three states allow a microservice to stay responsive, protect itself during failures, and recover safely when dependencies become healthy again.

Types of Failures Observed by Circuit Breakers

A circuit breaker does not only watch for exceptions. It watches for signs that a dependency is unhealthy or not behaving normally. In real microservices, dependencies can fail in different ways, so the circuit breaker monitors multiple failure signals. To make it easy to understand, you can think of failures in three main categories.

Hard Failures (Dependency is not reachable)

These are clear situations in which service is unavailable. Your service tries to call the dependency, but it cannot even connect.

Common examples:

- DNS failure (service name cannot be resolved)

- Connection refused (service is down or not listening)

- Socket/network errors (network break, connection reset)

- Service unreachable (routing issue, firewall, cluster issue)

In simple words: We can’t talk to the service at all.

Soft Failures (Dependency is reachable but unhealthy)

Here, the dependency is reachable but performs poorly—usually because it’s overloaded or has internal issues.

Common examples:

- Timeouts (service did not respond in time)

- Very slow responses (latency spikes)

- HTTP 5xx errors (server-side failures like 500, 502, 503, 504)

In simple words: The service is responding, but it’s struggling.

Special case: Rate limiting / throttling (depends on your rules)

Sometimes a dependency responds with:

- HTTP 429 (Too Many Requests)

This means the dependency is saying: I’m overloaded. Please slow down.

In distributed systems, a slow service can be more dangerous than a down service. A down service fails fast, but a slow service keeps your system waiting and slowly drains resources. That is why circuit breakers observe not just crashes, but any behaviour that makes a dependency unsafe to call.

Why Circuit Breaker Is Essential in Microservices

Here’s why it matters so much:

- It Prevents Cascading Failures: When a downstream service is failing, the circuit breaker temporarily stops calling it. This prevents one failing service from pulling down other healthy services.

- It Protects Your Service Resources: Slow or failing calls can block threads and hold connections for extended periods. Over time, your API becomes slow because it runs out of threads and available connections. A circuit breaker avoids this by failing fast.

- It Improves User Experience During Failures: A quick, clear response like “Service temporarily unavailable, try again” is far better than waiting 30–60 seconds and receiving a timeout. Fail-fast makes the system feel more predictable.

- It Enables Controlled Degradation: Even if a dependency is unavailable, your application can still function to some extent. For example, you can show cached data or partial data, or skip a non-critical step, instead of crashing the entire feature.

- It Helps Faster Recovery: By reducing calls to a struggling service, you give it breathing space to recover. This also helps autoscaling and restarts work effectively without being overwhelmed by continuous traffic.

Circuit breaker doesn’t prevent failures from happening—but it makes failures containable, predictable, and survivable. In production microservices, it’s not just a nice feature; it’s a stability requirement for any critical dependency.

Conclusion: Why Circuit Breaker Matters in ASP.NET Core Microservices?

A circuit breaker is like a safety switch in microservices—it protects your service when a dependency becomes slow or starts failing. Instead of letting requests wait, pile up, and spread the failure to other services, it stops harmful calls for a short time and keeps your API responsive. In short, a circuit breaker doesn’t remove failures, but it makes failures controlled, Predictable, and Survivable, which is exactly what a production microservices system needs.